“The Ethics of Adulthood in Times of Crisis” by Veronika Fuechtner

Today’s second contribution by Veronika Fuechtner, Professor of German at Dartmouth, is looking at the central role of children in “Mario and the Magician:“ In which way do kids communicate with other children across language barriers and how does their attention oscillate between overstimulation and boredom in Mann’s story?

The Ethics of Adulthood in Times of Crisis

Many readings of Mario and the Magicianhave connected it with Thomas Mann’s reading of Freud. The novella is thus often seen as an astute and timely analysis of the mass psychology of fascism. There are certainly many lines in it that resonate with today’s reemergence of authoritarian and xenophobic politics (not to mention how its’ language of contagion resonates in the times of Corona). Rereading this text, however, I was struck by what Mann actually chose not to engage with in Freudian theory, and that is Freud’s vision of childhood. To Freud, children are not innocent. They are self-interested, sexual beings. They might not fully appreciate what goes on around them, but they understand it on some level. To be sure, anything traumatic stays with them well before they acquire the means to articulate and process it.

InMario and the Magician, children play a central role, from the narrator’s two children, who charmingly disrupt everyday vacation life with their whims and whooping cough, to the “patriotic children” at the beach, who emulate the disturbing exclusionary politics of their newly fascist parents. In many ways, the narrative captures the experiences of childhood with great care. For example, the way in which kids communicate with other children across language barriers, or the way in which their attention oscillates between overstimulation and boredom. But the central premise of the novella seems strangely far-fetched. Would an eight-year old girl and her brother of roughly the same age truly believe – as the narrator suggests at the beginning of the novella – that a shooting they witnessed, was just part of a “play”? Would they not have picked up on how the adults around them were unsettled by the bizarreness and hostility of Cipolla’s performance? And would they not have reacted to the sense of humiliation and the protests of his subjects throughout the show, to the “indescribable commotion” after the shooting, the “ladies hiding their faces” and “shuddering,” the “mob” assaulting their real-life waiter friend Mario, and finally the arrival of the police?

Mann was a father to six children. And we know that he went through great lengths to get even minor details right to create fictional integrity. However, Mann’s narrator continuously emphasizes that his children “understood practically nothing of what had been said.” They are tremendously entertained by the way in which Cipolla eliminates “the gap between stage and audience.” And while the “sound of the voices made them hold their breath” during tense moments, they don’t pick up at all on their parents’ unease. These fictional children experience the adult world like the kids in Charles M. Schultz Peanutsuniverse – adult conversation is a comforting stream of wah wah wah. Moreover, they rarely do what most non-fictional kids do all the time: ask questions. They only ask two questions throughout the entire performance, namely how Cipolla’s numbers trick worked, and finally: “Was that the end, they wanted to know, that they might go in peace?” They are told yes, and then whisked away, and according to the narrator, their father, still untroubled to this day.

It can’t be accidental that Mann set aside personal and theoretical knowledge to craft these blissfully oblivious children that read so much younger through the eyes of their father than they are supposed to be. This is clearly a narrative device in service of a larger claim, and here, it might be helpful to consider Mann’s own statement that this novella is rather about ethics than about politics. Some readings of this novella have already pointed to the complicity of the narrator with Cipolla. The narrator is not merely exceptionally cranky, but also harbors deep-seated resentments and prejudices. He is in some ways a corrupt narrator. While he claims failure throughout the novella for not having brought the kids to bed in time and thus having exposed the entire family to Cipolla’s unsettling spectacle, his parental failure might lie somewhere else entirely. He fails to understand the richness and complexity of his children’s emotional and intellectual world. And he doesn’t provide them with any help to sort out the traumatic event they witnessed. The shooting, and one might add, this experience of the rise of fascism in a small Italian town, is just the beginning, and not the end, as the narrator tries to assure his children. Mann’s Mario and the Magicianpits a corrupt ethics of adulthood against the unacknowledged ethics of children, which entails a strong sense of curiosity, a capacity for boundless empathy, and a clear sense of the sexual nature of human relations. The narrator fails to take seriously the very insight that he shares with the readers about childhood: “Children are a human species and a society apart, a nation of their own, so to speak.”

Veronika Fuechtner

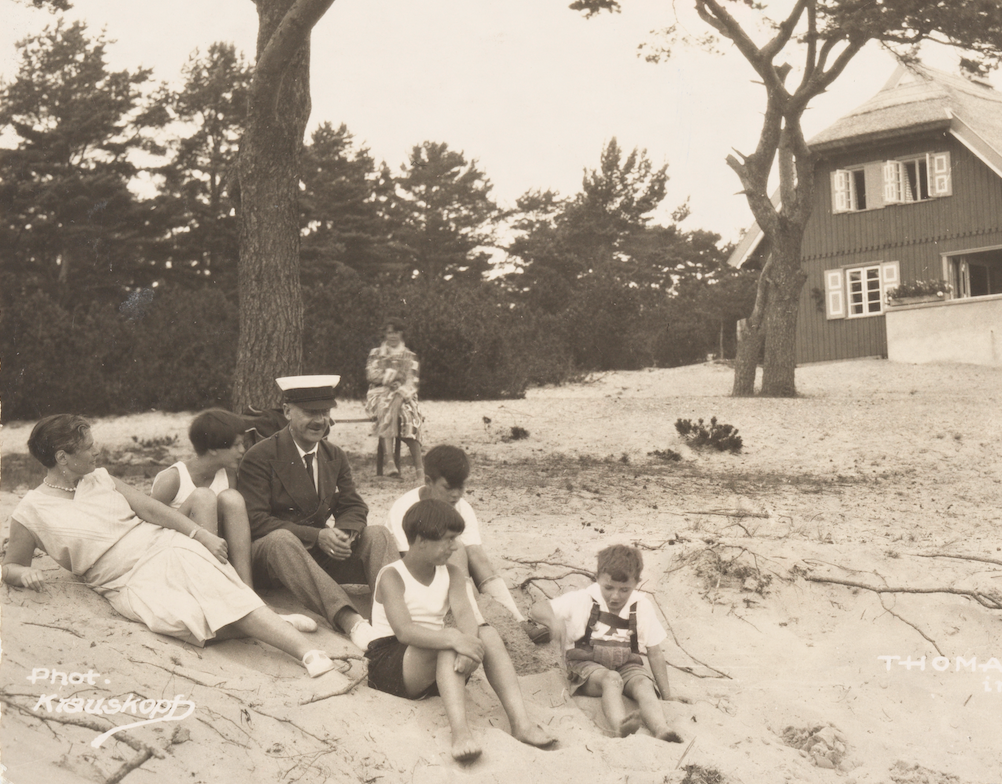

The photo shows Katia, Elisabeth, Thomas, and Michael Mann, and two unknown boys on a summer holiday in Nidden 1930. ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Thomas-Mann-Archiv / Photographer: Fritz Krauskopf

Reading this novella again after a very long time, what strikes me most is the strangely contourless narrator. Perhaps this discovery fits to Veronika Fuechtner’s remarks. On the first pages we are left completely in the dark about whom we entrust ourselves to. This is mainly because we learn so little about the narrator’s contact to his environment. All his interactions are motivated by the children: starting with the friendly contact to the hotel staff, to “waiters and bellboys”, to the “lust for the sea”, the funny-paranoid theory of an acoustic infection (a detail that particularly strikes us these days), the incident on the beach – up to the visit of Cipolla’s show. Basically, the narrator experiences the outerworld exclusively through the children’s eyes. They move back and forth between the social spheres like messengers, and he is forced to accompany them. This is an ambitious artistic approach, “kühn” is what Thomas Mann himself might have called it. Today, however, when I read on, it could also appear to me as a narrative deficit. I would like to come back to this later. In general, I find it increasingly difficult to read Mann’s prose with the same impact as my 25-year old self did. What bothers me today, for example, is the narrator’s pejorative portrayal of the Italians. This, too, can be seen not only as a deficit typical in Mann‘s generation, but also as an artistic one. I’m not sure where these questions will lead me to when we continue to read the novella.

Jan Bürger (Deutsches Literaturarchiv Marbach, Germany)

Thank you for this whole event and for these two fascinating contributions. One other thing that strikes me is that the text is addressed to “Sie/you” at moments when the narrator attempts to justify/excuse his complicity through failing to leave. At first I thought we might find out who this “you” is, but it appears to be the reader, so this rather colourless narrator is setting himself up for judgment by the reader. Just starting to think through the implications of this… Any thoughts?

Caroline Rowan-Olive

Open University/University of Reading, UK