“A Note on Endings” by Adrian Daub

It’s a wrap! Adrian Daub, Professor of Literature at Stanford, is ending our #MutuallyMann initiative with “A Note on Endings.“ As the novella marks the end of a decade, as well as the beginning of new horrors, Daub writes: “After all, it’s unclear the novella really could or should end, because such an ending would to some extent constitute a liberation from the atmosphere it describes.“

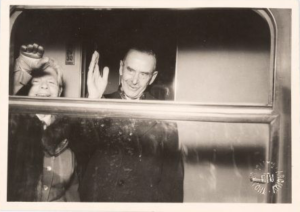

Thomas and Katia Mann waving goodbye, Lübeck in 1955. ETH-Bibliothek Zurich, Thomas-Mann-Archiv.

“Yes, we assured them, that was the end,” Mann tells us at what is the end of “Mario and the Magician,” but was only the beginning of the atmosphere the novella so deftly sets out to capture. The sheer skill with which Mann conjures the atmosphere around incipient fascism poses problems for the novella’s ending. After all, it’s unclear the novella really could or should end, because such an ending would to some extent constitute a liberation from the atmosphere it describes. “An end of horror, a fatal end. And yet a liberation – for I could not, and I cannot, but find it so.”

As Donna Rifkind noted in her blog entry for #MutuallyMann, the end of “Mario and the Magician” is where Mann departs from the “Erlebnis,” the factual “travel experience” referred to in the novella’s German subtitle. Thomas Mann did go to see a magic act in real life, and a young man was humiliated during the performance. The act of violence that closes the novella, however, was suggested by his daughter Erika Mann. At the same time that closing flourish throws a spotlight onto Thomas Mann himself, the other great magician-figure in “Mario’s” orbit.

The denouement of “Mario” relies on a trope that had stood the writer in good stead for a long time, although, like Cipolla’s act in “Mario,” it had become perhaps a bit shopworn by the time Mann dusted it off to close “Mario.” So many of the young Mann’s short fiction centered around stage performances that turned cataclysmic. “Luischen” (1900) culminates in a sadistic burlesque in which the lawyer Jacoby realizes he is being cuckolded by his wife as she forces him to perform in public. “Blood of the Wälsungs” (written 1906), where a visit to a Wagner-opera inspires an incestuous liaison. Mann’s story of an itinerant performer and his nightly performance finds Mann himself digging deep into his own bag of tricks.

The young Mann had been fascinated by the moment in which a performer loses their unselfconsciousness – sometimes it’s literally hypnotic, for instance in “The Clown.” And while young Mann links unselfconsciousness to being an artist, he does not by that token valorize it. The eponymous wunderkind of his 1903 short story is able to forget his audience because he doesn’t respect it in the least, “an indistinct mass of humanity.” That concern predated “the atmosphere of Torre di Venere” by decades; “Mario” is a story about the 30s told in tropes of the fin-de-siècle.

Why this trip back in time? Because Mann’s own myth-making around “Mario,” his insistence that the novella is about fascism in some way can blind us to the way in which the novella is just as much about some of Mann’s most persistent themes. If he’s going with the times in one respect, raising the pressing issues of the day, in others he’s almost regressing. “Mario” is another artist novella, another meditation on theatricality, another dramatic turning point relying on homoeroticism. But besides all of these, the novella is also about fascism.

I think this is what makes this text such a great, if upsetting, read. As the 1930s wore on, the idea that traditional aesthetics were no longer sufficient to think through the unprecedented challenges posed by fascist inhumanity, became fairly widely accepted. Mann’s is one of those works that tries to grapple with that unprecedented challenge using fairly traditional formal means. The story is about a narrator constantly threatening to tear himself away, but never quite managing to.

Short fiction often has something of a legerdemain – it compresses a lot into very little. This of course is what the narrator of “Mario and the Magician” wants to do with the oppressive atmosphere and the figure of Cipolla: condense it all into the Cavaliere. I think it’s unclear whether we’re supposed to take the narrator’s attempt absolutely seriously. After all, both the mode of his narration (constantly protesting that he did not want to witness what he again and again decides to witness) and the philosophy Cipolla expounds on stage (that acting in obedience and forcing your will on others “all came to the same thing”) seek their salvation in concentrating the atmosphere, the “voiceless common will which was in the air” into the Cipolla-figure. Cipolla’s violent, even melodramatic, end strongly suggest that this hope only works in fiction. The real-life “tragic travel experience” – as the many reactions to our #MutuallyMann reread on social media attest – may be here to stay.