“Evasive Depth: Germany and the Germans” by Meike G. Werner

German Studies Scholar Meike G. Werner on Tilman Riemenschneider, Eduard Berend and the fate of political persecution.

Photo: Tilman Riemenschneider, 1460-1531. Probably self portrait (detail of Creglingen altarpiece).

“That’s just utter nonsense.” So said Eduard Berend, editor of the works of Jean Paul, in a soft but decisive voice, when he heard yet again the often repeated genealogy: Luther, Friedrich II, Bismarck, Hitler. Berend’s comment was as cool and clear as the day, May 29, 1945, on which Thomas Mann spoke at the Library of Congress and developed a very similar line of thinking in his famous lecture, Germany and the Germans.

Berend would return to Germany in 1957 after seventeen years of Swiss exile in order to complete the historical-critical edition of the works of Jean Paul at the new literary archive in Marbach. Berend had begun his edition of the complete works in 1927, honoring a German writer whom some critics even today place above Goethe, and who shared none of the anti-Jewish prejudices of Weimar’s Olympian poet. Under pressure from Germany’s race laws, the Prussian Academy of Sciences had terminated Berend’s contract at the beginning of November 1938. Only a few days later, in the wake of nationwide anti-Semitic violence of the November Pogrom, the Nazis transported Berend along with thousands of other Berlin Jews to Sachsenhausen. After release from the concentration camp, Berend spent the following year attempting to escape, and in December 1939 was at last able to flee to Switzerland, where, from his impoverished circumstances in Geneva, he witnessed the deterioration of Germany into a genocidal nation.

In Germany and the Germans, Mann suggests that the collapse of civilization in Hitler’s Third Reich might best be understood as a reversal of German inwardness. In itself a “highly valuable, positive trait,” this inwardness was “transformed into evil by a sort of dialectic inversion,” becoming, in Mann’s interpretation, its own nationalist and imperialist opposite. Berend wasn’t having any of this speculative drivel. His concerns were immediate. After the end of the war, Berend searched for his brother Franz and his sister Anna every day, scouring daily “the lists of surviving Jews from camps or elsewhere, but without success and without hope.” The Nazis had shunted Franz from Hamburg to Lodz on October 24, 1941, and on May 12, 1943 deported him from there to the extermination camp at Chelmo. On February 26, 1943, they deported Anna from Berlin to Auschwitz.

In his famous talk, Mann refers to Nazi “crimes” but never calls the death camps or the persecution of the Jews by name. Yet he had detailed knowledge concerning the Nazis’ relentless persecution of European Jews, as his diaries and the texts of the BBC radio broadcasts in which he addressed his fellow Germans beginning in 1940 show. Mann was indeed well informed about almost all of it: about the torture of prisoners in the camps, about the many suicides, about the cattle cars, about the mass gassings, and about the bloated corpses of Jews starved to death in the Warsaw ghetto. He also knew about the stacks of human remains bulldozed into mass graves, and about the piles of confiscated clothing, eyeglasses and children’s shoes. And he knew about the crematoria and the chimneys, about Majdanek and Auschwitz- Birkenau.

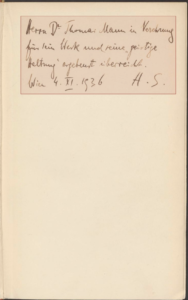

Photo: Book Tilman Riemenschneider im deutschen Bauernkrieg with a dedication by Heinrich Steinitz to Thomas Mann, 11/04/1936. Source: Thomas Mann Archive

Yet his artistic interpretation (emerging from the context of writing Doctor Faustus) is a descent, a katabasis, into the depths of German cultural history: into the gothic medieval past of his own home city of Lübeck, and into the age of the Reformation. Wittenberg stands at the outset of Mann’s diagnosis, which runs from Luther through all manner of failed uprisings, and then to Bismarck and Hitler. Where is Thomas Mann, and what he knows, in all of this? Telling perhaps is that Mann finds the germ of a counternarrative in the lone figure of Tilman Riemenschneider, perhaps the greatest limewood sculptor of the northern Renaissance, if also long forgotten and rediscovered only in the nineteenth century. Like Mann, Riemenschneider took the side of liberty and justice, sympathizing with the peasants in 1525 against the bishops and princes of Würzburg. But unlike Mann, Riemenschneider paid a bitter price. Arrested and tortured, the great artist “emerged from the ordeal as a broken man, incapable thereafter of awakening the beauties in wood and stone.” In Riemenschneider’s fate, Thomas Mann plainly glimpsed a version of what could have happened to him had he stayed in Germany. Unlike the broken and long forgotten Riemenschneider, Mann could continue to compose works of great artistic value at his desk in Pacific Palisades. He could also become a political writer—“against my nature and my will,” as he confided to his friend and supporter Agnes E. Meyer—whose works, especially when centered on a critique of German Innerlichkeit, counted as influential contributions to understanding Germany and the Germans. Only, to Berend and perspicacious others, the interpretation no longer made sense.

“Mann refers to Nazi ‘crimes’ but never calls the death camps or the persecution of the Jews by name. Yet he had detailed knowledge concerning the Nazis’ relentless persecution of European Jews, as … the texts of the BBC radio broadcasts … show.”

So what you’re saying is that Thomas Mann didn’t sufficiently condemn the Shoah in one of his speeches, which we know that he very well could have done given that he … condemned the Shoah in many a prominent speech.

You undermine your own argument.

It would be presumptuous for me to say what Thomas Mann should have said.

My intent was to lend an ear to contemporary voices, like those of Eduard Berend. There were many others. Let Hannah Arendt and Karl Jaspers stand for many, as Jaspers wrote to Arendt in early December 1945:

»Whether it will be necessary to distance oneself from Thomas Mann’s ethical and political views is a question that troubles me. I value him so highly as a writer and novelist that I would be reluctant to say anything against him. But if the confusion he is causing here is not cleared up, we will have to find some response to his attacks and behavior – because he is a German and is speaking as a German. If the response is to be meaningful, it has to be thorough. One would have to go back as far as his essay of 1915 on Frederick the Great (which pained me as much at the time as his present effusions do now.) But one should also be familiar with his radio talks.«

And then Arendt’s reply on January 29, 1946:

»The Thomas Mann book – the radio talks and a Neue Rundschau with another essay on this subject (a particularly unpleasant one, it seems to me) – is in the mail. It really is absurd to take him seriously politically, important as he is as a novelist – except that he does exert a certain vague influence.«

(in Hannah Arendt Karl Jaspers Correspondence 1926–1969, ed. by Lotte Kohler and Hans Saner; translated from the German by Robert and Rita Kimber. San Diego, New York, London: A Harvest Book Hartcourt Brace & Company, 1992, p. 27 and p.32)

Thank you very much, Meike G. Werner, for your contribution. Well, calling the explanation given by Thomas Mann of “evasive depth”, a “speculative drivel” not making sense for those having been “perspicacious“ , cannot remain unchallenged. I am wondering what you are having in mind Thomas Mann should have had said in order to be “non-evasive”, “non-speculative” and more “perspicacious”. Was there any other person having presented a better explanation of what has happened?