“Becoming German through Goethe” by Veronica Fuechtner

Veronica Fuechtner, German scholar at Dartmouth College, on the Brazilian roots of the Mann family and the writers’ sense of belonging.

Becoming German through Goethe by Veronica Fuechtner

Reading Thomas Mann’s 1945 speech Germany and the Germans seems rather timely now as Germany has been shaken by racist and anti-Semitic attacks in Hanau and Halle. In the past few years, openly expressing extreme right-wing thought has become more socially acceptable. Demonstrators against the government measures to curb the Corona pandemic march alongside Neo-Nazi groups and yet compare their activism with the political resistance against National Socialism. The absurdity of these alignments probably wouldn’t have been lost on Mann. At the end of WWII, he faced the hostility of those writers who had stayed in the Third Reich, as some of them cultivated a strong sense of victimhood and accused émigrés like Mann of having turned their back on Germany. Mann had to contend with the fact that not everyone would welcome him back, neither to Munich nor to Lübeck, the “remotest nook of Germany, where I was born, and where after all, I belong.” (47) As Mann stood in front of his audience at the Library of Congress, speaking as “an American to Americans,” he claimed many belongings. He had been a Czech citizen, he just had become a US-American “citizen of the world,” he had experienced worldly and multilingual Switzerland, and most importantly, despite — or rather with — reservations, he presented himself as a German-born intellect, who couldn’t simply renounce the “wicked, guilty Germany.”(48)

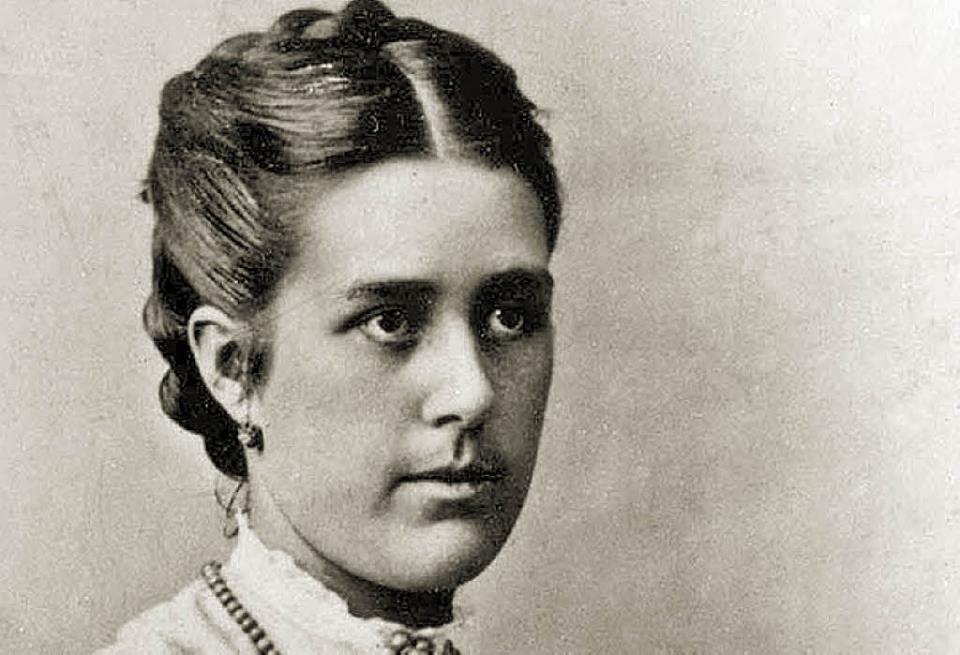

One sense of belonging that he had previously claimed in other contexts is missing here, namely his connection to Brazil, the homeland of his mother, Julia Mann, née da Silva Bruhns. Thomas Mann intimately knew the Brazil of her narrations, and he was keenly aware that his “mai” always longed for what she thought of as her childhood paradise. Barely two years before writing Germany and the Germans, Mann had called Brazil his “motherland” and described himself as “a German writer with Brazilian blood,” whose artistic program was influenced by “the Latin American blood in my veins.” While he claimed this belonging in a private letter to the journalist and theater director Karl Lustig-Prean, he chose not to claim it in this very public discussion of how to engage with Germany post-1945. We are left to speculate on the reasons, but one part of the answer might probably lie in the addressees. With Lustig-Prean, who sought Mann’s support for the “Movement of Free Germans in Brazil,” it was clearly important to Mann to validate anti-fascist resistance in Brazil not just with his moral support, but with his family connection.

For his US-American listeners at the Library of Congress, however, claiming “Brazilian blood” might have confused his aim to present himself as an embodiment of US-American as well as German cosmopolitanism. Therefore, the way in which the immigration history of his Brazilian mother shaped Thomas Mann’s understanding of Germanness remains unspoken here. But to me, his mother’s story resonates between the lines, particularly in the way Mann evoked Goethe in this vision of German cosmopolitanism. It goes without saying that Goethe held a special place for him and this is not the only instance where he argues that for Goethe, Germanness meant the affirmation of the “super-national, world-Germanism, world-literature” against the “barbaric racial element” of German patriotism. (57)

Mann’s reading of Goethe had its beginnings in the conversations with his mother. Julia Mann, who learned German at age seven in a process that she herself described as extremely arduous, became an enthusiastic reader and connoisseur of the German-language literary canon, particularly of Goethe’s works. For her son’s 30th birthday, she presented him with Albert Bielschowsky’s highly influential Goethe biography, which described Goethe’s life as an expression of the morality of a genius. Thomas Mann worked his way through this Goethe biography innumerous times – like no other Goethe book in his life. Julia Mann also maintained a collection of clippings and notes about Goethe, which her son inherited and consulted for his Goethe novels, particularly Lotte in Weimar and Doctor Faustus, which he was writing as he worked on Germany and the Germans. A 1921 article from this collection by the feminist literary scholar Elise Dosenheimer characterized the significance of Goethe as follows: “In Goethe we see the highest symbol, the highest realization of everything that is part of the idea of Germanness.” This “German essence” that morally transcends the political rhetoric of the day, that becomes “timeless,” as Dosenheimer wrote, connects to Mann’s idea of Goethe as a national writer with universal appeal: one that astutely and critically explores the dark side of the German soul while embodying its best possibilities, its worldliness.

Germany and the Germans ultimately draws from the works of Jewish-German scholars, not only Dosenheimer or Bielschowsky, but also others like Heinrich Teweles or Felix Theilhaber, who in different ways helped Mann to construct an ideal of Goethe that could not be co-opted by National Socialism. Their “outsider as insider” perspective, as the historian Peter Gay has famously phrased it, reflected the Jewish enthusiasm for Goethe, in times when Jews could not fully belong – even when they could become citizens. To some extent this perspective was shared by Julia Mann, who never quite belonged, and who tried to make very sure that her son would be able to claim the world of German-language culture without a doubt as to where he belonged. Ironically, this is not how things turned out, and this speech makes this very clear. Towards its end, Mann went so far to suggest that Goethe wished for a diaspora of Germans “in order to develop the good that lies in them.” (65) What Mann didn’t say, is that he was not only a part of such a German diaspora, the community of émigrés from National Socialism, most of them Jewish, but also one of its most well-known representatives. While his mother claimed her Germanness in Germany with her embrace of Goethe, Mann claimed his Germanness through Goethe most forcefully once he left Germany behind, never to return.

Photo: Julia da Silva-Bruhns as a young woman.

Thank you, Veronica Fuechtner, for your contribution and the very interesting side-aspects delivered therein.